Updated October 28th, 2015: The County has issued the reclamation plan for the Breezy Point mine. Click HERE to read it — pay special attention to the conditions that they have specified.

… and here’s the memo I wrote requesting that they deny the permit. All of the slope issues that I’m complaining about still exist, so we still have some work to do peepul.

PETITION TO DENY MEMO

To: Brooke Muhlack – Buffalo County, Land Conservation Director

CC: Douglas Kane – County Board, Chair

Nettie Rosenow – County Board, Land Conservation Committee Chair

Sonya Hansen – County Administrative Coordinator

From: Marcie and Mike O’Connor

Re: Breezy Point Mine Reclamation Plan – petition to deny

Date: August 14, 2015

There is a fundamental and substantive error in the analysis that underlies the reclamation plan proposed for the Breezy Point mine. The first part of this memo will demonstrate this error and explain why the plan as written must be rejected.

We follow that analysis with detailed comments describing additional deficiencies in the plan. At no time should these comments be viewed as support for the CUP Application (which is included in the reclamation plan by attachment).

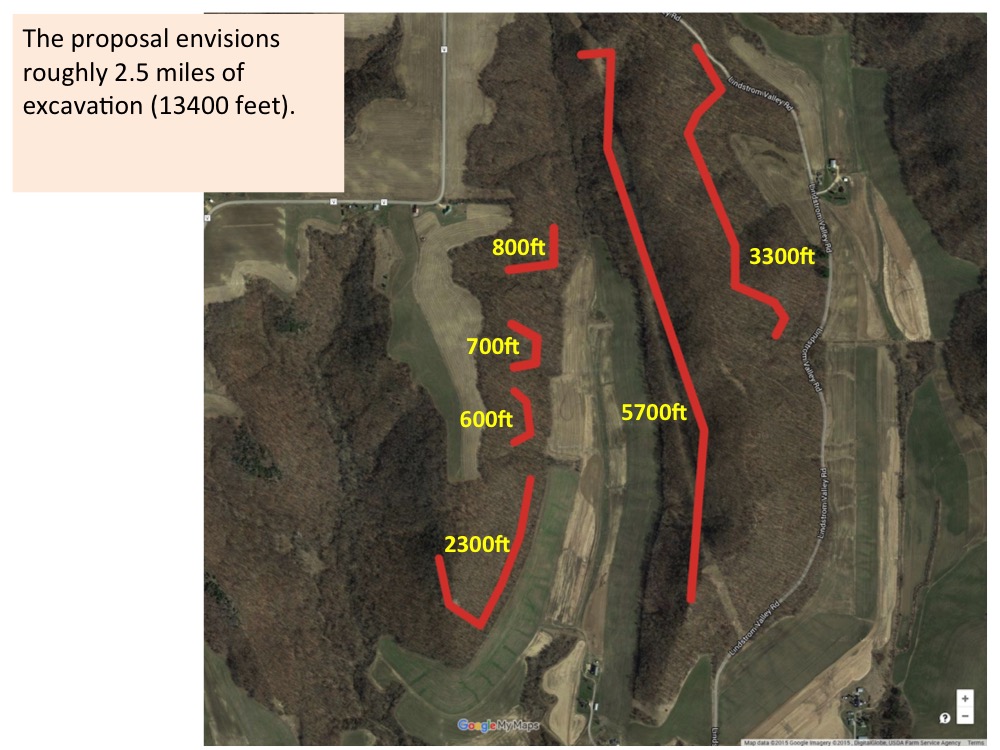

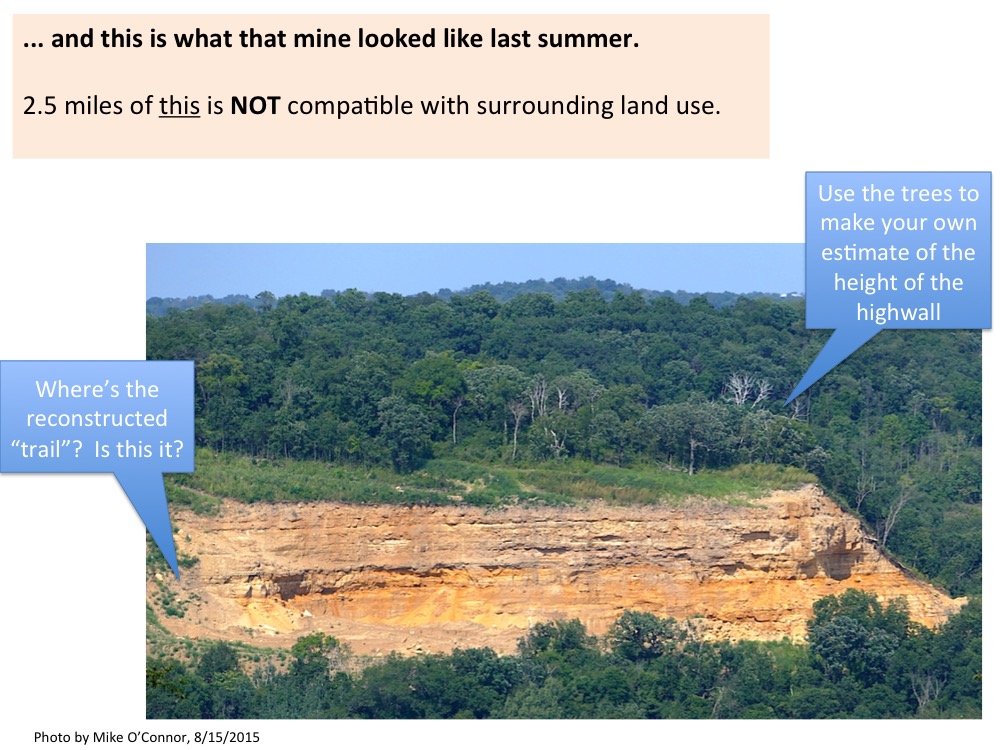

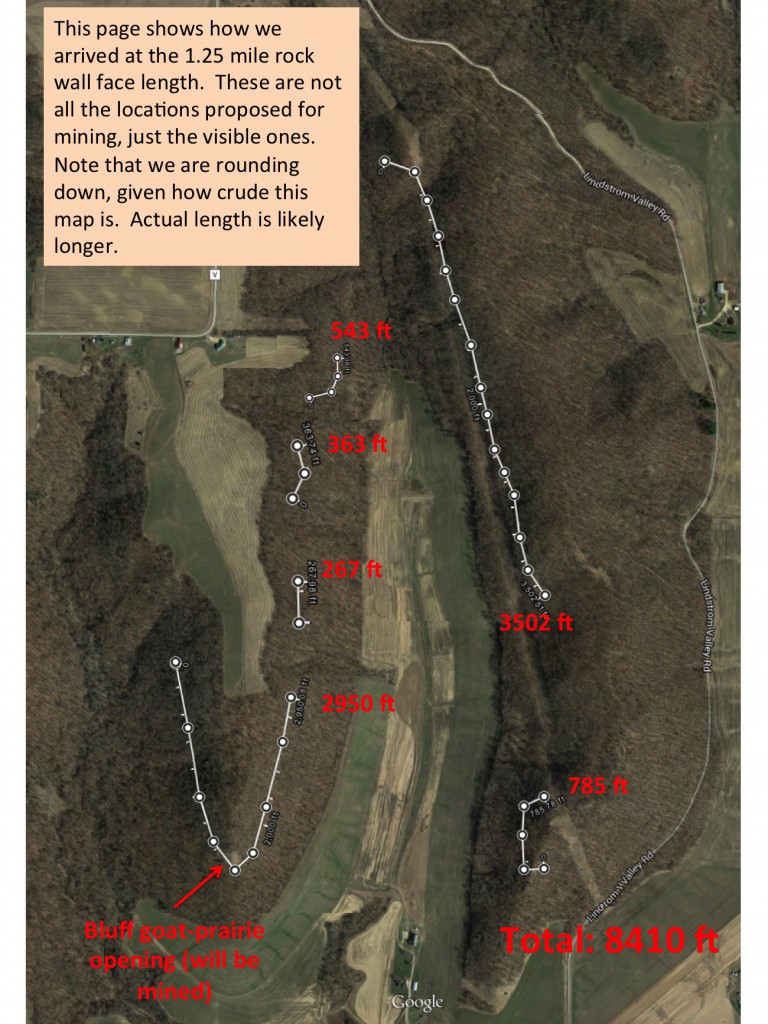

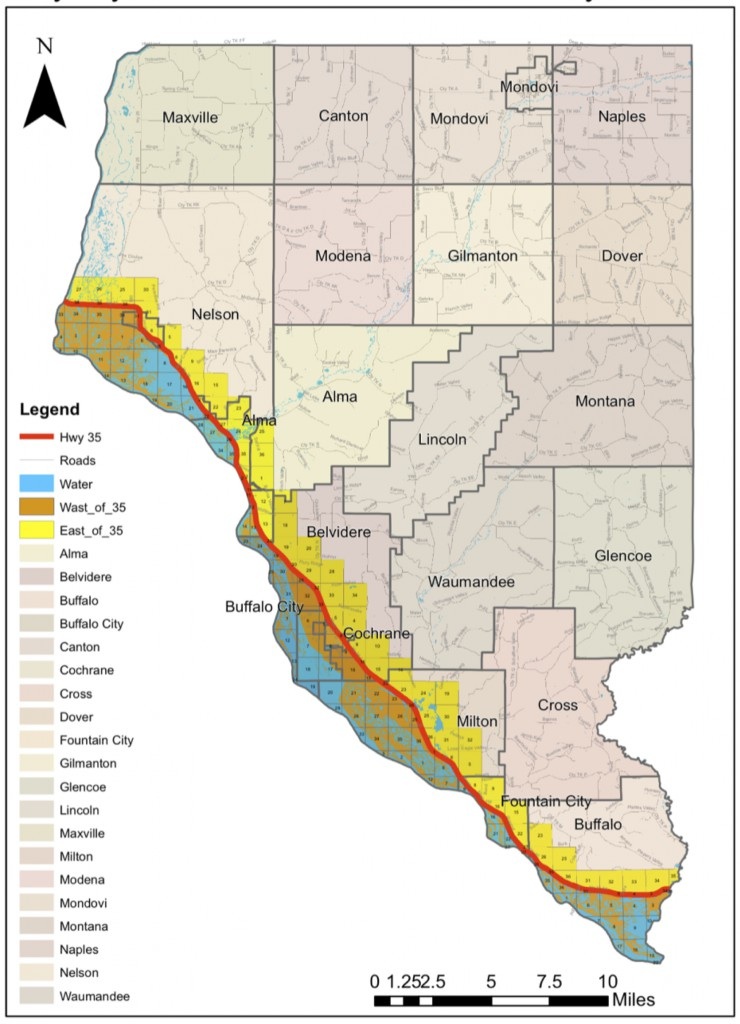

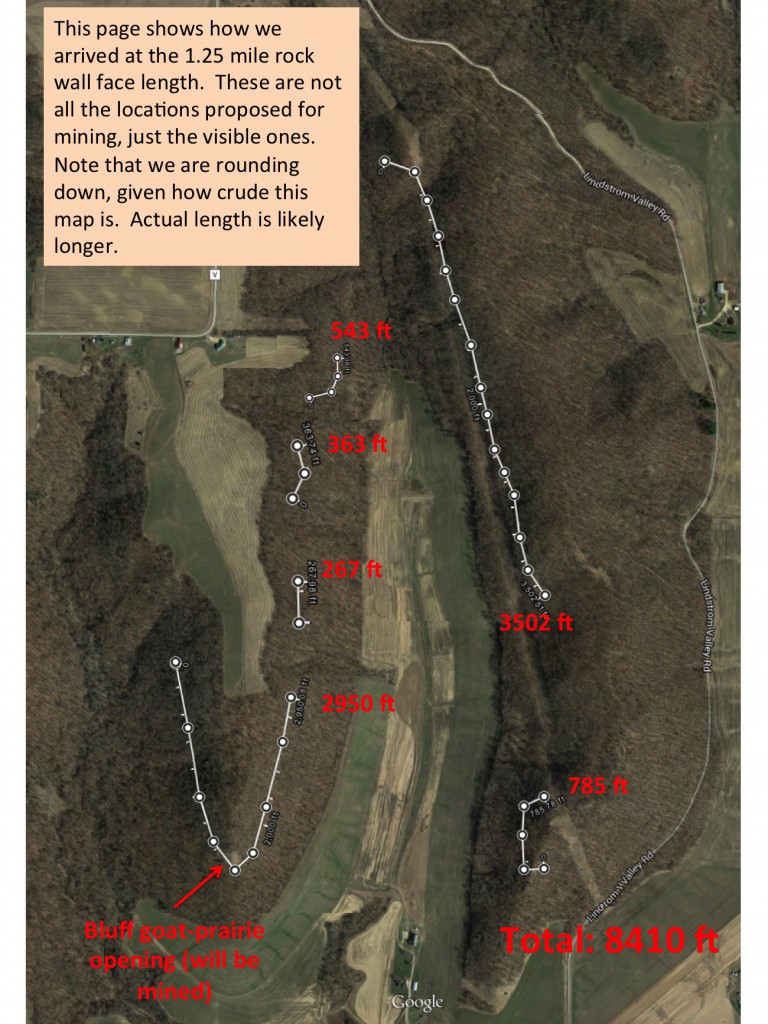

Replacing 30 acres of rare Driftless Area bluff-prairie and oak-savanna habitat with low-diversity prairie plantings described as a “bluff trail” that will not be visible to anyone except the property owners is completely incompatible with surrounding land use and should not be permitted. In addition, this plan proposes at least 1.25 miles of sheer 100+ foot rock faces in the Steep Soils district that will be visible for miles.

Respectfully submitted,

Marcie and Mike O’Connor

Petition to deny the Breezy Point reclamation plan

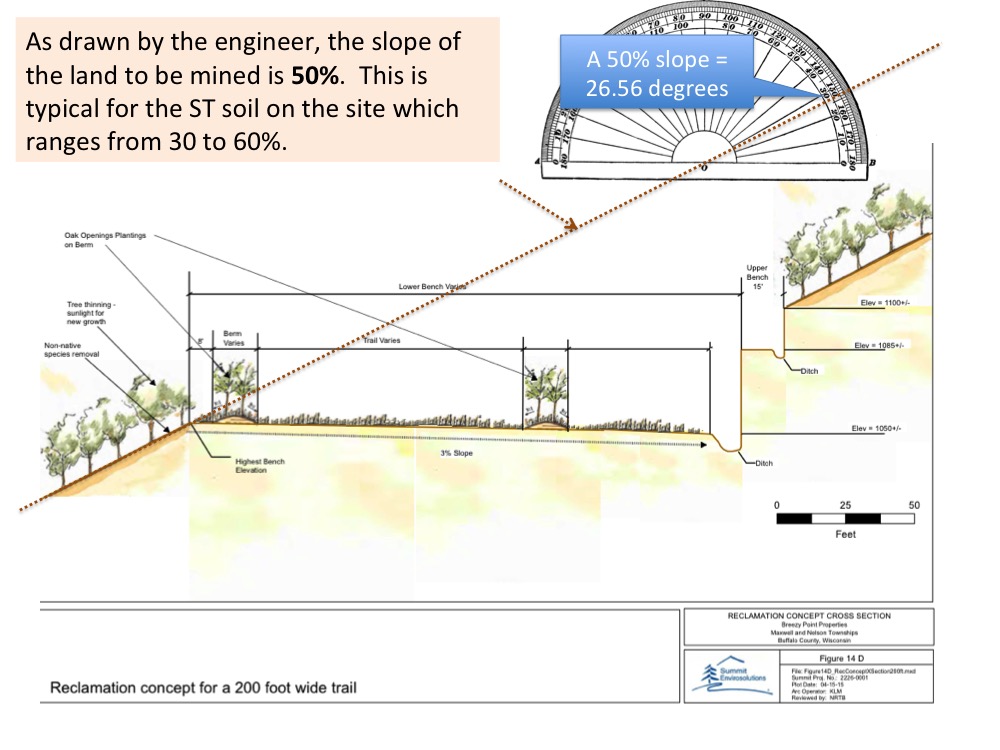

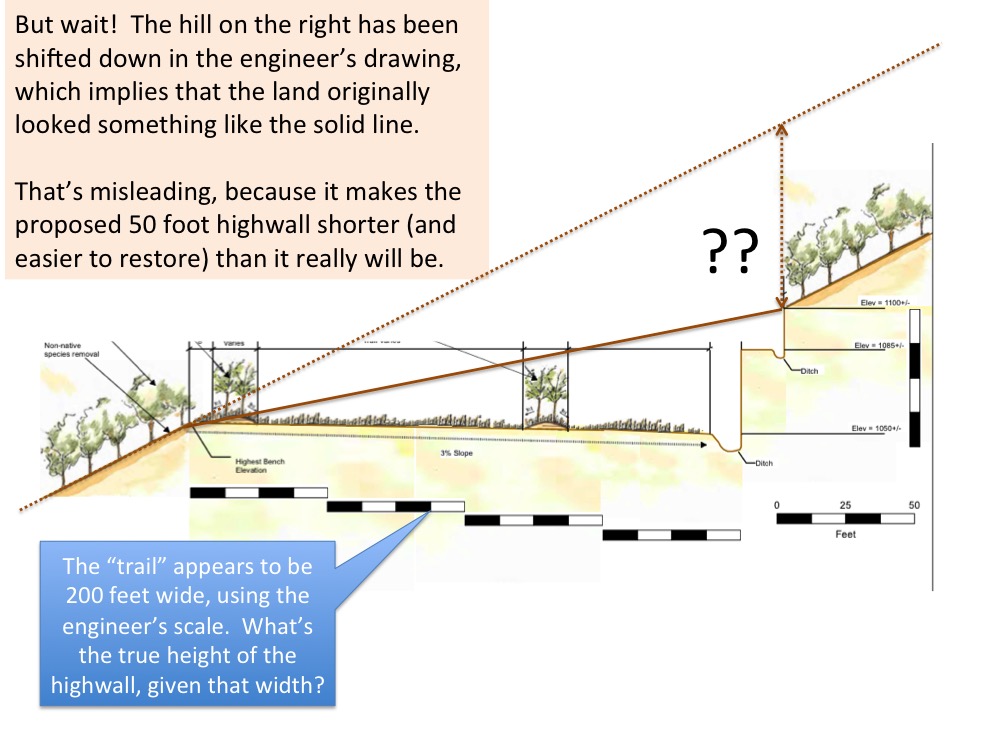

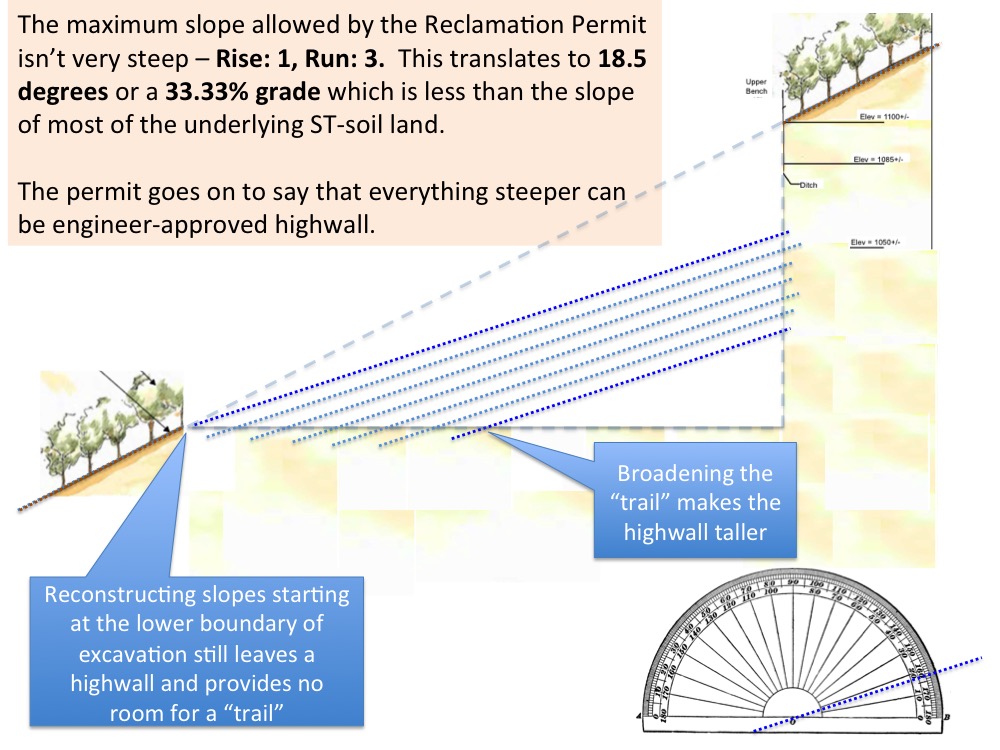

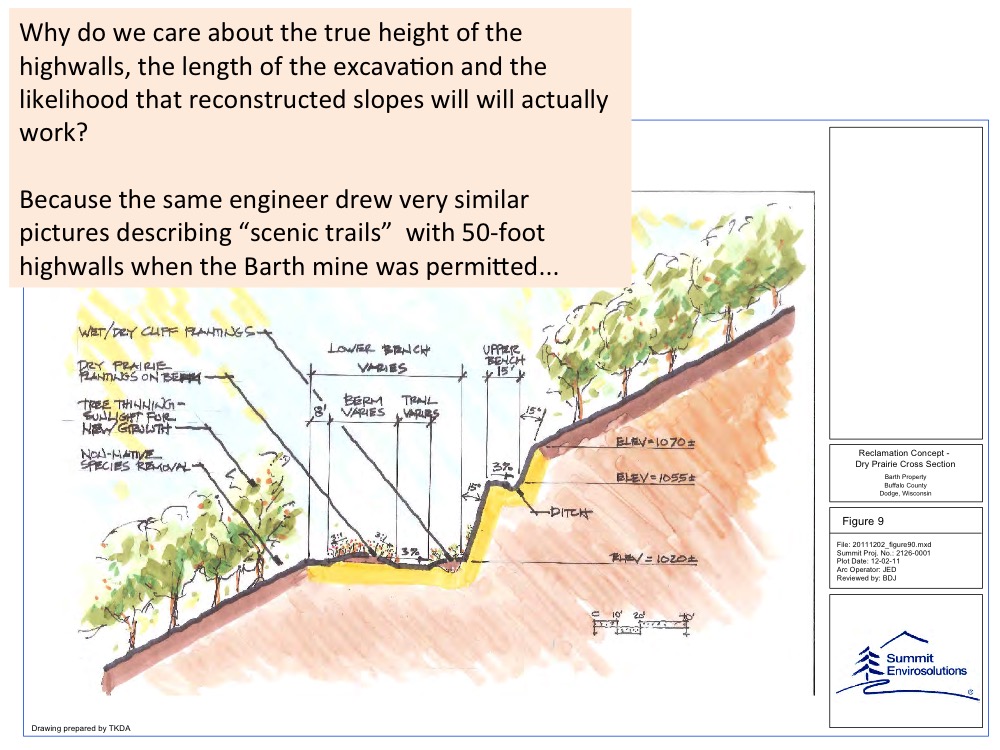

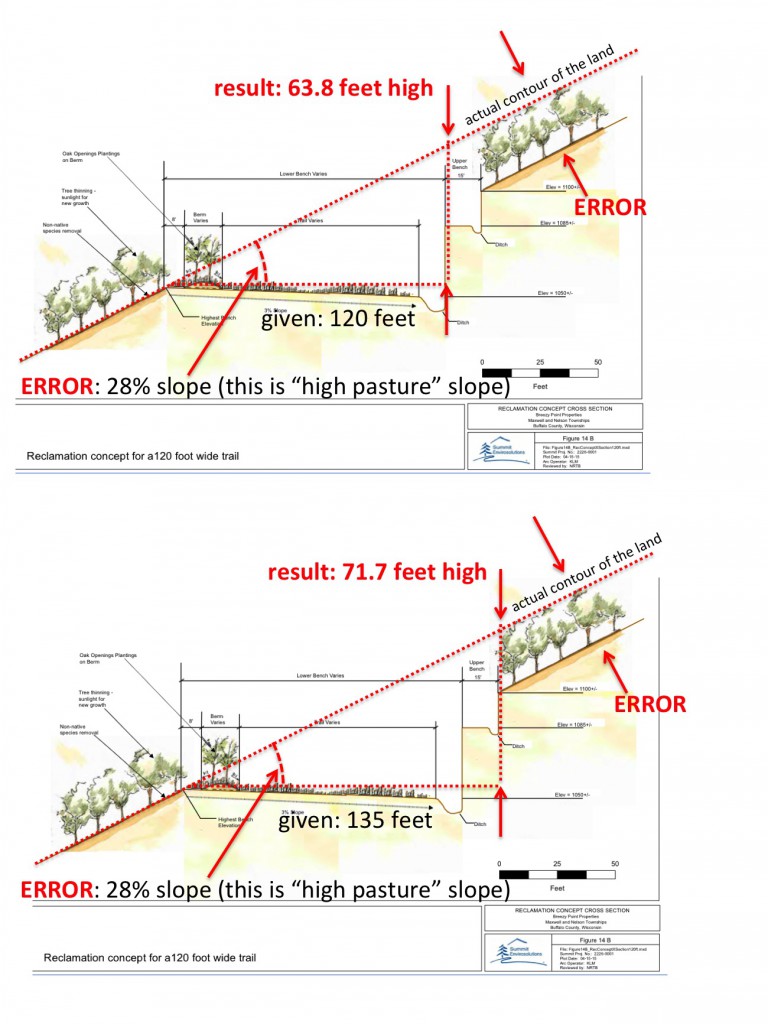

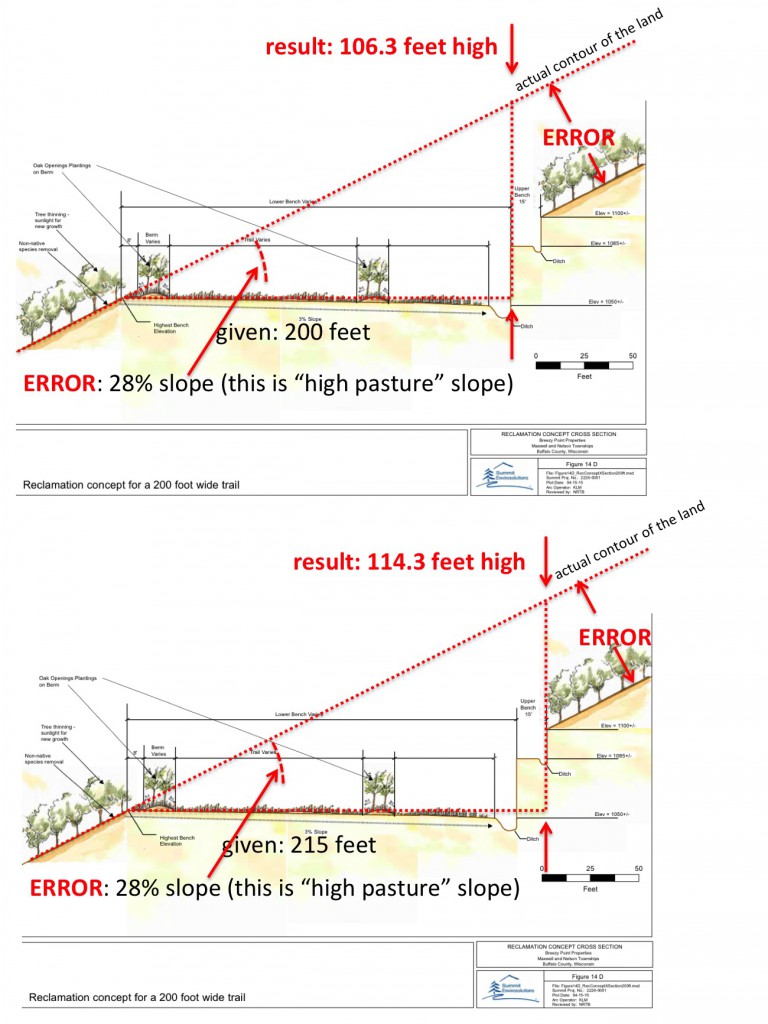

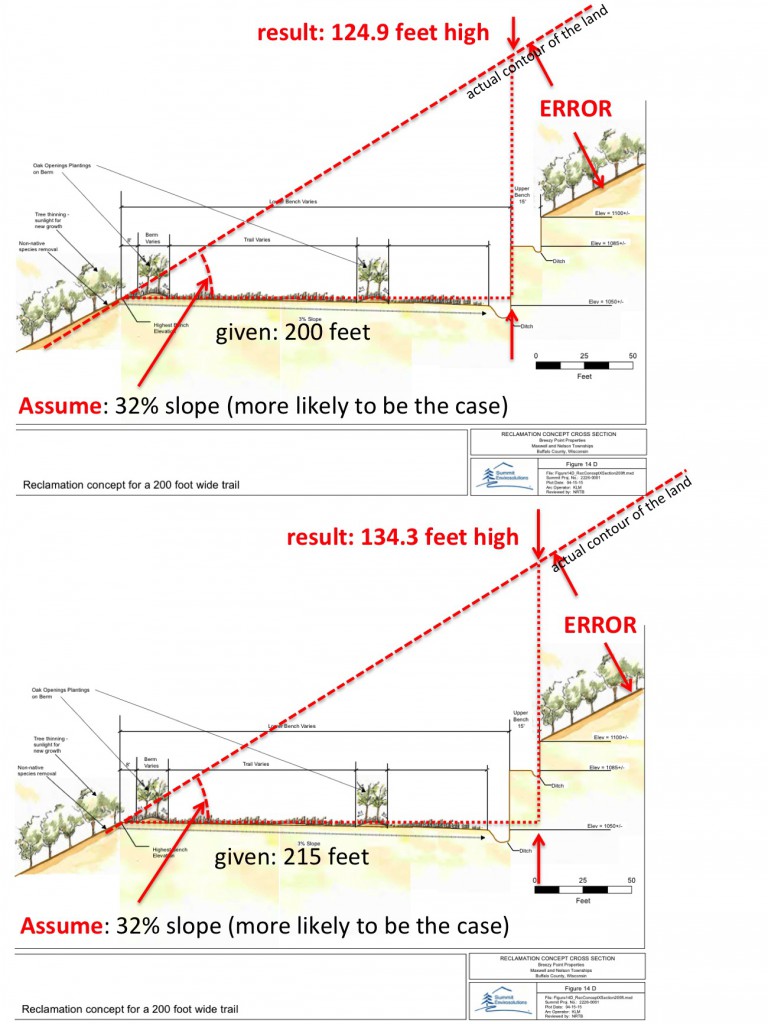

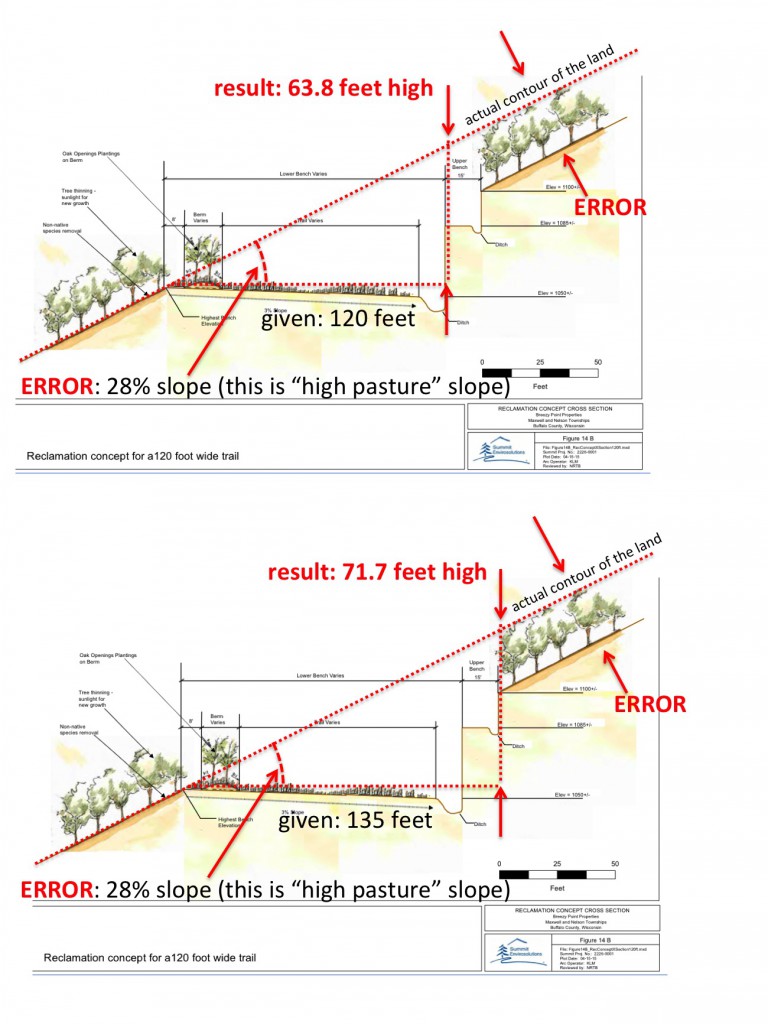

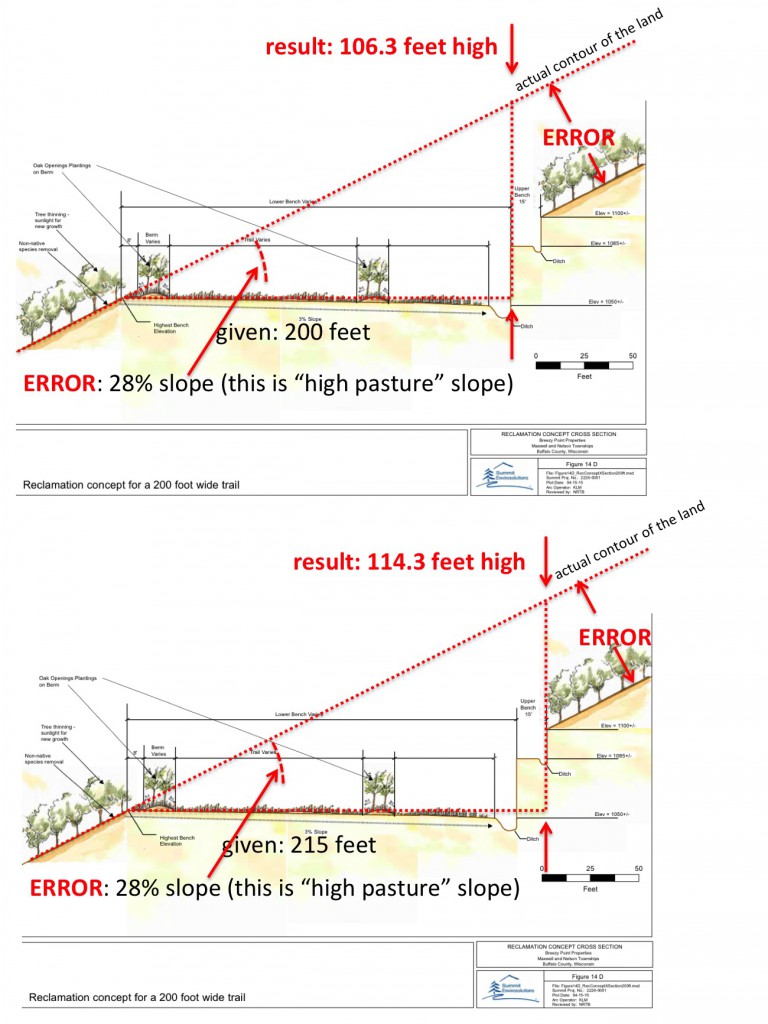

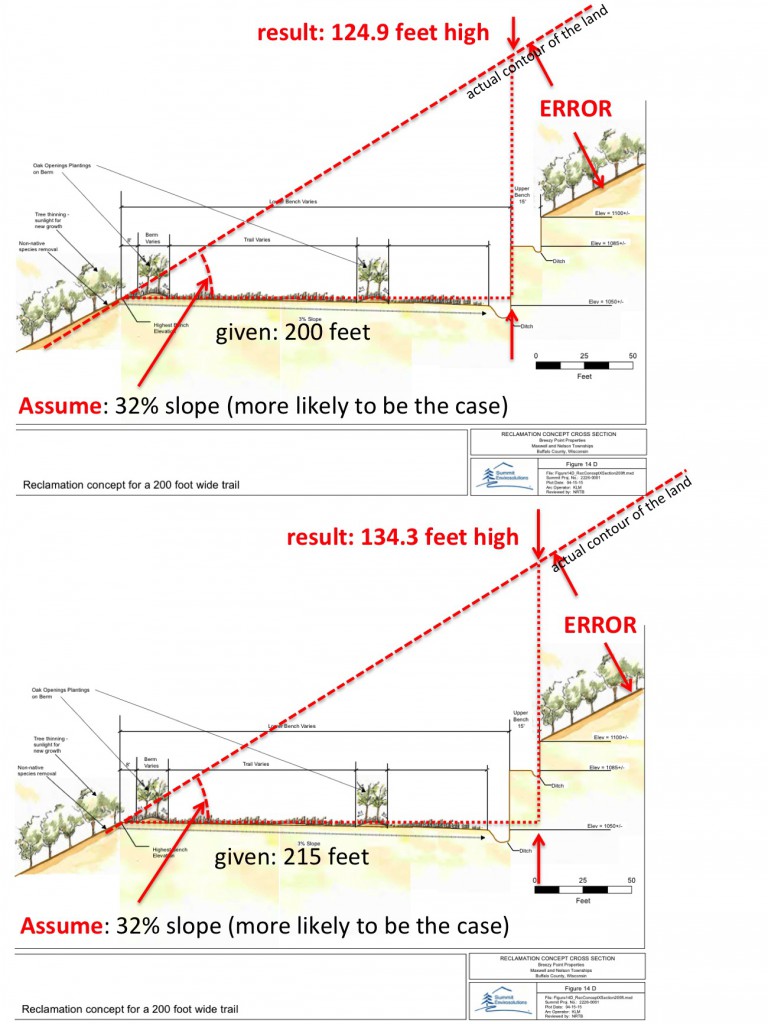

The reclamation plan provides drawings that imply that the vertical rock faces behind the trail will total no more than 50 feet – a 35-foot lower section and a 15-foot section that is set back by 15 feet.

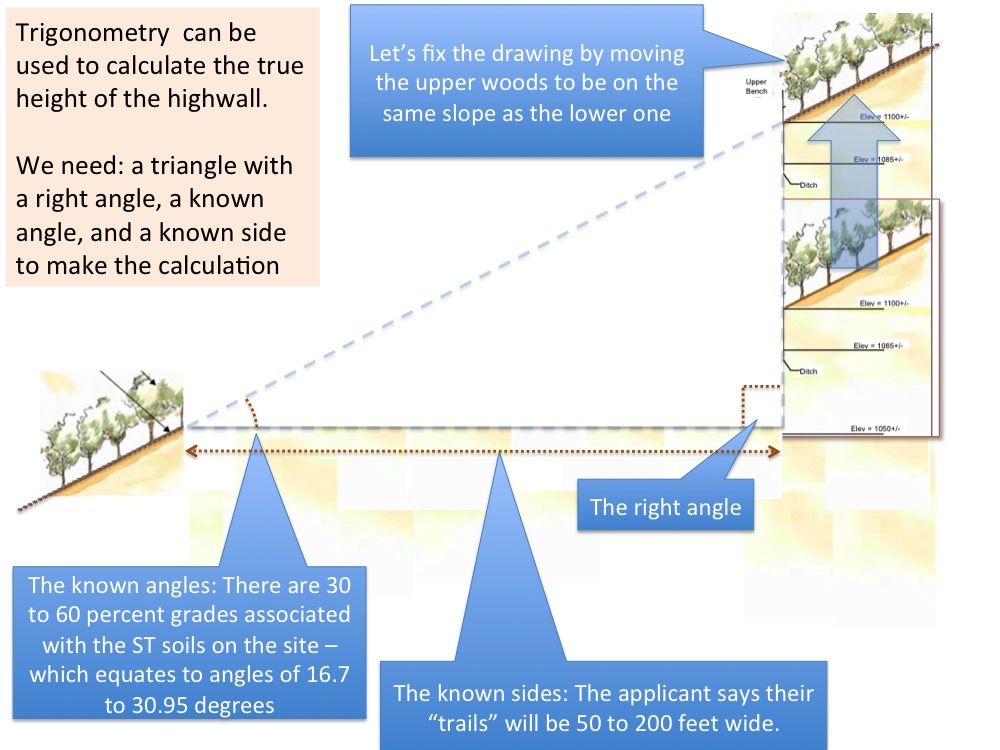

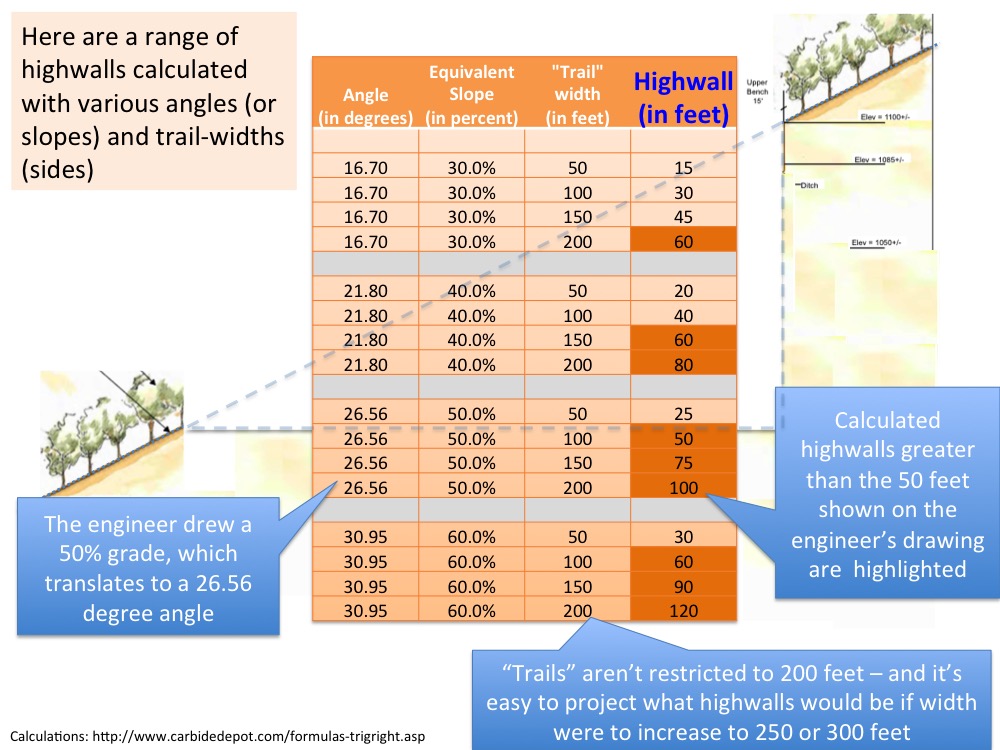

The following diagrams demonstrate that this is an error and show that the vertical rock faces will more than likely range from 70 to 130 feet high or more, depending on trail width and terrain. We presume this is merely a mistake on the part of the consultants preparing the plan and not a deliberate attempt to mislead county citizens and decision makers.

Here is the fundamental error. Trail designers did not account for the actual contour of the land when describing the rock face. Rather, they shifted that contour back so that in all cases the height of the rock face is the same 35 plus 15 feet. We used basic trigonometry to demonstrate that error on the following pages.

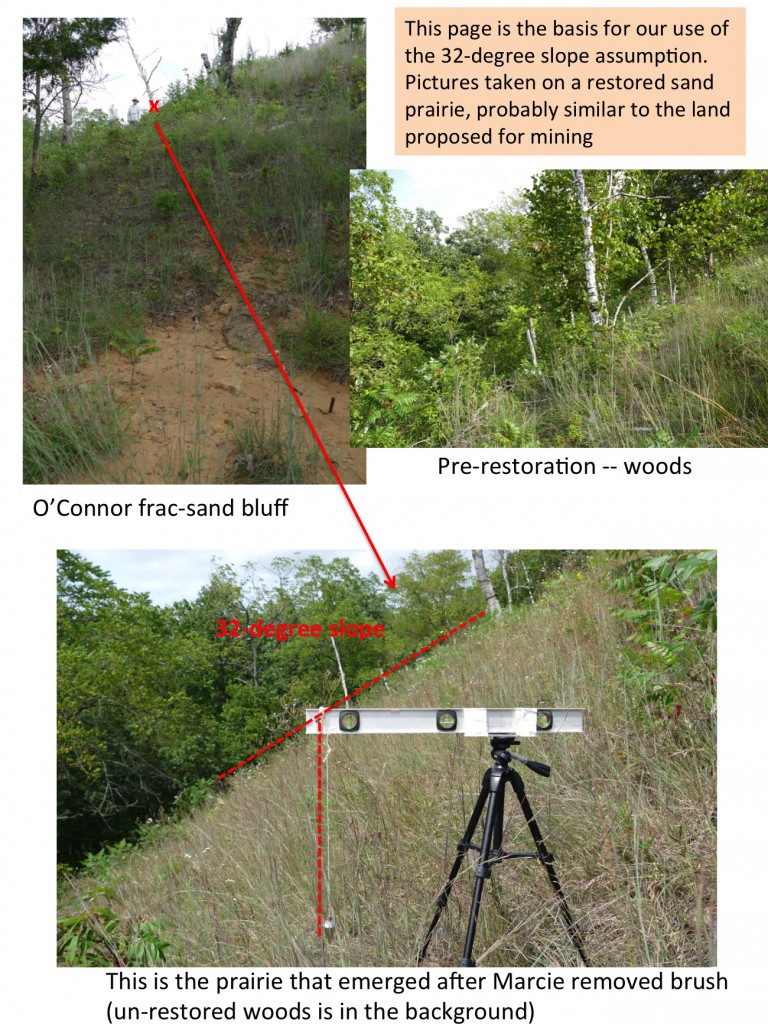

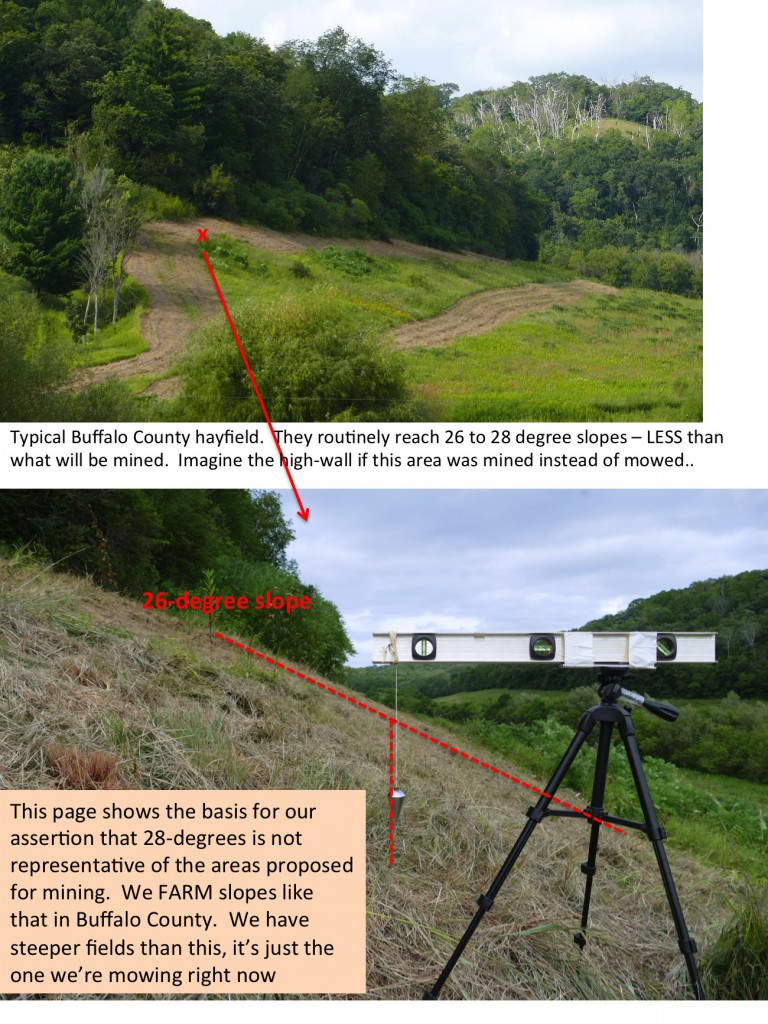

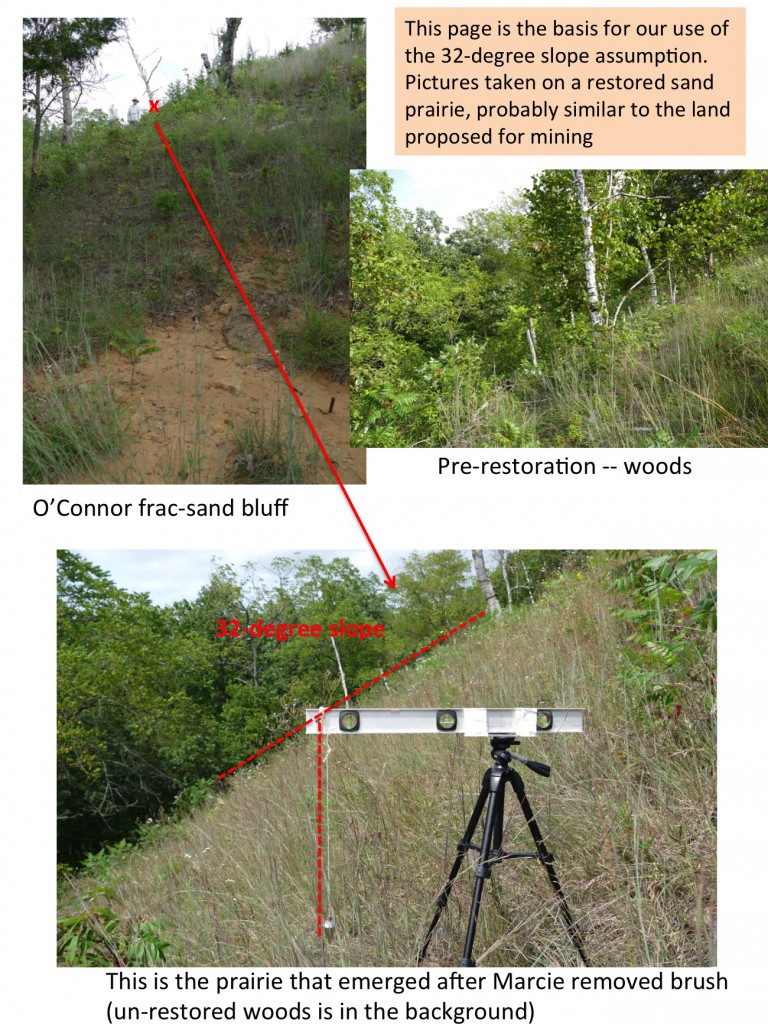

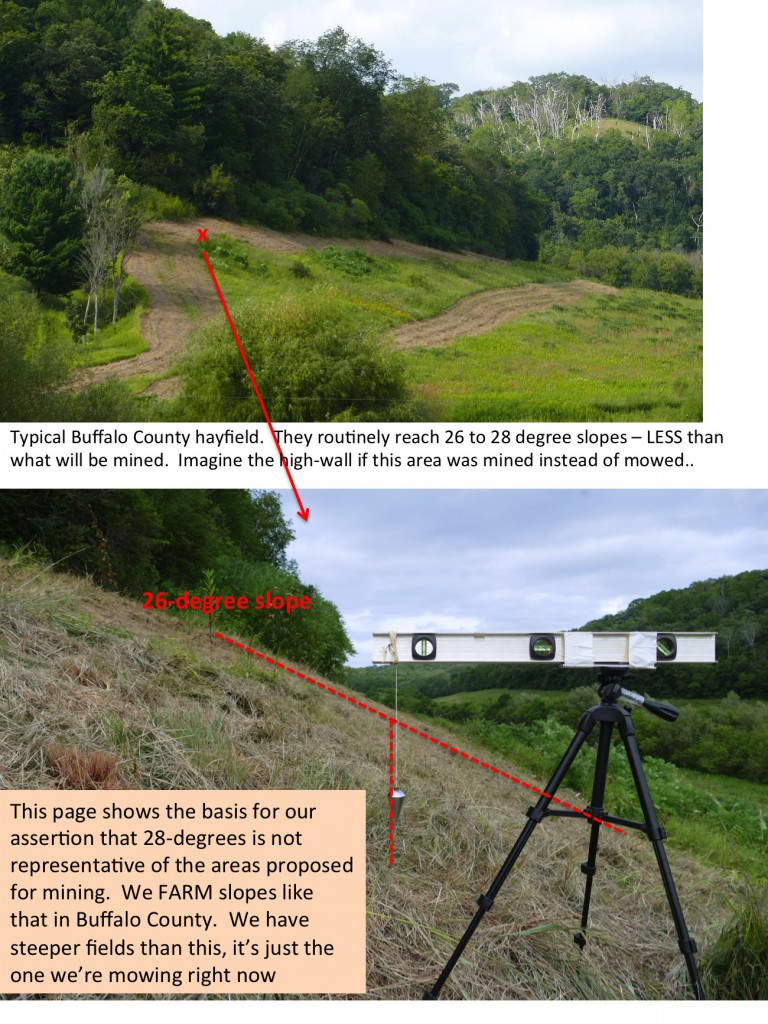

An additional error compounds the first. Trail designers used a constant 28% grade to describe the underlying terrain. This is wrong in two ways. A 28% grade is more typical on the “high side” of pastures in the centers of Driftless Area valleys as we will demonstrate with pictures of a pasture from our farm. Secondly, the contours of the land are not a constant slope. Slopes generally increase closer to the ridge-tops where mining will take place.

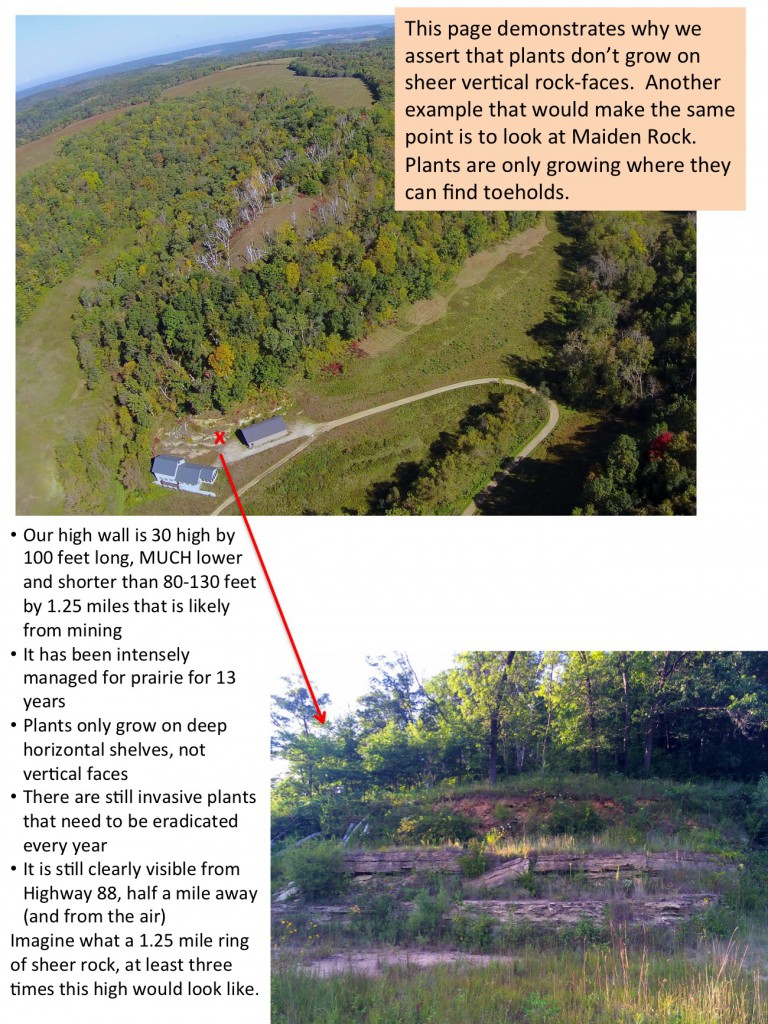

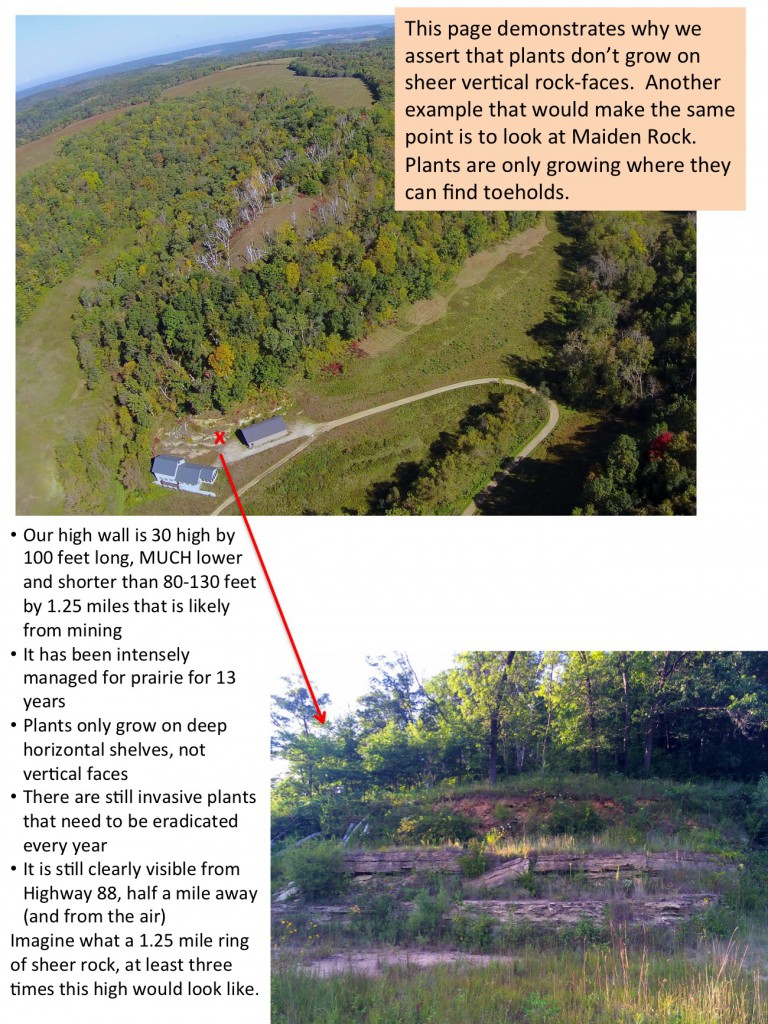

The final error is the presumption that sheer vertical rock-faces can be successfully planted. We will use pictures of a very small rock face on our property to demonstrate that plants don’t grow in vertical bare rock; they grow in horizontal terraces, nooks and crannies. Yet this design specifies two sheer vertical rock faces, with no slope whatsoever, behind the mined area.

Taken together, this means that the rock face will be much higher than is implied, and it will be bare. For this reason, the plan must be denied and these errors corrected before proceeding with the application process.

We request a written justification from the Land Conservation office if this reclamation is approved as drafted.

————————–

————————–

———————————

———————————

——————————————

—————————————— ———————————

———————————

—————————————–

—————————————–

—————————————

—————————————

Detailed commentary on the Breezy Point reclamation plan

Financial Assurance

The reclamation plan states on Page 1, “the current and projected price of the sand beneath the mined area makes this project possible.” We suggest that those words may have been written some time ago. The need for proper financial assurances for this project is crucial and that without them, there is substantial risk that this plan will not be completed.

Most of the permitted frac sand mines in Buffalo County are either in bankruptcy or shut down, primarily due to the fact that there is no market for commodity sand that carries a substantial non value added trucking cost penalty. Buffalo County citizens and residents are already facing the prospect of unreclaimed mines.

The most recent example is the Bechel mine in Pepin County, which recently closed and left the township with a crushing financial burden.

Given the high probability that this mine will also fail financially, the financial assurances for this project need to be ironclad and funded up front. “Pay as you go” financial-assurance instruments, as provided for by DNR regulations, must not be allowed.

Project Goals

The application also states on Page 1 that the goal is to “restore the terrace to pre-settlement vegetation consisting primarily of dry prairie species, oak openings, and wet- and dry-cliff plantings.”

Change the goal of restoration from “pre-settlement vegetation” to “pre-settlement habitat.” Pre-settlement vegetation can be accomplished by simply planting a small number of species that were here in pre-settlement times. By changing the focus to “habitat”, we recognize that the goal is to reconstruct a rare ecosystem that has been destroyed.

A list of existing (pre-restoration) species that have been identified in the bluff prairies and savannas of our nearby farm is included in Appendix A. It is very likely that a survey of the Breezy Point site would find many, if not all, of these species in the degraded savanna that is being proposed for mining.

Appendix B is a much more representative sampling of the DNR “Wisconsin Natural Heritage Working List” than the one provided by the applicant. Note that we have found many of those species on our farm a few miles away. Also note that we have found those species in places very similar to the ones that are proposed for destruction by this mining project.

Once again, note that the applicant proposes to destroy rare, unique, diverse habitat that may support well over 100 species of plants and the soil that underlies them. This is why we request changing the project goal from merely planting a few plants that existed here to attempting to restore a diverse habitat that roughly approximates that which is being destroyed.

Project Methods

These comments are derived from lessons we’ve learned from the 500-acre native habitat restoration and reconstruction project we are doing on our nearby farm. Our land shares many of the same featuresof the land that is being proposed for mining – degraded savanna woodlands, bluff prairie points, wetlands, etc.

While these suggestions will not result in habitat quality comparable to that which is being destroyed, the result will at least be better than the office-park landscaping that is being proposed.

Increase the diversity and density of the plantings to improve the probability of establishing the plant species that are found in comparable environments in the county.

The reclamation plan specifies mixes according to NRCS Critical Planting Code 342 and Wisconsin Agronomy Technical note 5. These mixes are in no way representative of the habitat that is being destroyed by mining Driftless Area bluff prairies and savannas found in Buffalo County.

Appendix 3 is an example of the seed mix we used when “reconstructing” prairies by planting into old crop fields. Here is a photo of the field that was planted using this mix – 8 years after planting. Note that while there are many prairie plants, there are still invasive plants that we need to manage.

Specific recommendations on seed mix:

– Increase the density of plantings from 60 seeds per square foot to a minimum of 80 seeds per square foot. 100-120 seeds per square foot would be preferable given the budget resources available.

– Increase the seeds-per-square-foot ratio of forbs to grass

o Current plan: equal number forbs and grass per square foot

o Recommended: 75 forbs seeds per square foot, 15 grass seeds per square foot

Heavy-grass mixes like the one proposed will result in a prairie with very few forbs because the grasses are more aggressive and will crowd out the slower-developing forbs.

– Increase the pounds-per-acres ratio of grass seeds to forbs seeds in the mix

o Current Plan: 80% grass to 20% forbs by weight

o Recommended: 50% grass to 50% forbs by weight

Again, roadside and office-park erosion-control plantings that are heavy on grass are a fine thing. But Buffalo County savannas are known for the predominance of forbs and the mix that is proposed in no way resembles the diversity of the plants being destroyed.

– Increase the number of species being planted from the proposed 20-25 to 80-100 (as seen in our mix)

– Increase the number of forbs species being planted, again along the lines of the mix that we used on this prairie.

– Use local seeds (originating no more than 75 miles from the site, preferably within 25 miles of the site).

Cliff Face

The high wall must be graded and terraced, rather than vertical, in order to provide footholds for plantings.

We planted this 30-foot high post construction cliff-face about 15 years ago on our property. Note that the vertical portions of the cliff are still bare after all that time. This is why the proposal to leave a sheer vertical high wall behind the mined area is unacceptable. A 1.25-mile long vertical bare-rock scar on the landscape, visible for miles around, will never heal no matter how many seeds are planted on it.

The high wall must have slope and terraces where cliff-plantings can take hold. This photo shows that the vast majority of the plants are finding flat places to take root.

Top Soil

Do not use topsoil in areas of native plantings. The proposed reclamation plan mentions that topsoil that is removed during mining operations will not be used in areas of native plantings. We commend this approach. The degraded savanna soil now has a large seed bank of invasive species that will completely dominate the plantings if used in native-habitat restoration areas. This is exacerbated because the soil will be radically disturbed, which encourages the growth of weeds.

Using this disturbed soil as the basis for native plantings will dramatically reduce the quality of the restoration and increase the difficulty of controlling invasive plants to near impossible. Rather, use removed topsoil in other areas of the restoration and use near-sterile overburden and non-specification sand for the native-habitat restoration area.

Invasive Species Control

Dramatically extend the period of invasive-species control. A minimum of 10 years should be required, 15 is preferred, in order for native species to be able to withstand encroachment by invaders. Provide resources for periodic review and repair for an additional 5 to 15 years.

Specify A Qualified Contractor To Do the Restoration

An independent contractor, with a proven track record of native habitat restoration, should be hired to perform the restoration. Prairie Restorations (http://www.prairieresto.com/) is an example of such a company. Native habitat restoration is a skill claimed by many and mastered by few — thus the need for a proven record of accomplishment of success at such restorations.

Annual Review and Course-Correction

Specify that an annual audit of restoration activities be performed by independent organization (not the mine operator, nor the restoration contractor) and that the recommendations made during this audit are binding on the operator and the contractor.

Appendix 1 – Existing Prairie and Savanna Species Observed on the O’Connor Farm

Agalinis aspera Rough False Foxglove

Amelanchier laevis Smooth Serviceberry

Amorpha canescens Leadplant

Andropogon gerardii Big Bluestem

Anemone cylindrica Thimbleweed

Anemone quinquefolia Wood Anemone

Anemone virginiana Tall Thimbleweed

Antennaria neglecta Field Pussytoes

Antennaria plantaginifolia Plantain-leaved Pussytoes

Apocynum androsaemifolium Dogbane

Apocynum cannabinum Indian Hemp

Aquilegia canadensis Wild Columbine

Arabis lyrata Sand Cress

Artemisia campestris Wormwood

Asplenium platyneuron Ebony Spleenwort

Asclepias exaltata Poke Milkweed

Asclepias syriaca Common Milkweed

Asclepias tuberosa Butterfly Milkweed

Asclepias verticillata Whorled Milkweed

Asclepias viridiflora Green-flowered Milkweed

Aster ericoides Heath Aster

Aster laevis Smooth Aster

Aster lateriflorus Calico Aster

Aster oblongifolius Aromatic Aster

Aster oolentangiensis Sky-blue Aster

Aster sagittifolius Arrow-leaved Aster

Aster sericeus Silky Aster

Astragalus canadensis Canada Milk-vetch

Botrychium dissectum Dissected Grape-fern

Bouteloua curtipendula Side-oats Grama

Bouteloua hirsuta Hairy Grama

Bromus kalmii Prairie Brome

Bromus latiglumis Ear-leafed Brome

Calystegia spithamaea Low Bindweed

Campanula rotundifolia Harebell

Carex pensylvanica Pennsylvania Sedge

Castilleja sessiliflora Downy Yellow Painted Cup

Ceanothus americana New Jersey Tea

Cirsium altissimum Tall Thistle

Cirsium discolor Field Thistle

Commandra umbellata Bastard Toadflax

Corallorhiza odontorhiza Autumn Coralroot

Coreopsis palmata Prairie Coreopsis

Crataegus sp. Hawthorn

Cypripedium parviflorum Yellow Lady’s Slipper

Dalea purpurea Purple Prairie Clover

Desmodium canadense Showy Tick-trefoil

Elymus canadensis Wild Rye

Elymus hystrix Bottlebrush Grass

Elymus trachycaulus Slender Wheat Grass

Eragrostis spectabilis Purple Lovegrass

Erigeron pulchellus Robin’s Plantain

Eupatorium purpureum Purple Joe-pye Weed

Euphorbia corollata Flowering Spurge

Fragaria virginiana Wild Strawberry

Gallium boreale Northern Bedstraw

Gentiana alba Cream Gentian

Gentiana quinquefolia Stiff Gentian

Geranium maculatum Wild Geranium

Geum aleppicum Yellow Avens

Geum canadense White Avens

Geum triflorum Prairie Smoke

Gnaphalium obtusifolium Sweet Everlasting

Hedeoma hispida Rough Pennyroyal

Helianthemum bicknellii Hoary Frostweed

Helianthus occidentalis Western Sunflower

Heliopsis helianthoides False Sunflower

Heuchera richardsonii Prairie Alumroot

Hieracium kalmii Canada Hawkweed

Hieracium scabrum Rough Hawkweed

Hypericum pyramidatum Great St. John’s Wort

Hypoxis hirsuta Yellow Star Grass

Krigia biflora False Dandelion

Kuhnia eupatorioides False Boneset

Lathyrus venosus Veiny Pea

Lechea intermedia Pinweed

Lechea stricta Prairie Pinweed

Lespedeza capitata Round-headed Bush Clover

Liatris aspera Rough Blazing Star

Liatris cylindracea Cylindrical Blazing Star

Linum sulcatum Yellow Flax

Lithospermum canescens Hoary Puccoon

Lithospermum incisum Fringed Puccoon

Lobelia spicata Spiked Lobelia

Monarda fistulosa Monarda

Muhlenbergia cuspidata Prairie Satin Grass

Muhlenbergia racemosa Upland Wild Timothy

Oenothera biennis Evening Primrose

Oxalis violacea Violet Wood-sorrel

Packera paupercula Balsam Ragwort

Panicum oligosanthes Few-flowered Panic Grass

Pedicularis canadensis Wood Betony

Physalis heterophylla Clammy Ground Cherry

Physalis virginiana Virginia Ground Cherry

Polemonium reptans Jacob’s Ladder

Polygala sanguinea Field Milkwort

Polygala polygama Purple Milkwort

Polygala verticillata Whorled Milkwort

Potentilla arguta Prairie Cinquefoil

Prenanthes alba Lion’s Foot

Prunus americana Wild Plum

Prunus pumila Sand cherry

Pycnanthemum virginianum Mountain Mint

Ratibida pinnata Yellow Coneflower

Rosa sp. Wild Rose

Schizachyrium scoparium Little Bluestem

Scrophularia lanceolata Figwort

Sisyrinchium campestre Blue-eyed Grass

Solidago flexicaulis Zig-zag Goldenrod

Solidago missouriensis Missouri Goldenrod

Solidago nemoralis Gray Goldenrod

Solidago ptarmicoides White Goldenrod

Solidago rigida Stiff Goldenrod

Solidago speciosa Showy Goldenrod

Solidago ulmifolia Elm-leaved Goldenrod

Sorghastrum nutans Indian Grass

Spiranthes magnicamporum Great Plains Lady’s Tresses

Sporobolus heterolepis Prairie Dropseed

Stipa spartea Needle Grass

Taenidia integerrima Yellow Pimpernel

Thalictrum thalictroides Rue Anemone

Tradescantia ohiensis Common Spiderwort

Veronicastrum virginicum Culver’s Root

Viola x palmata Early Blue Violet

Viola pedata Birds Foot Violet

Viola pedatifida Prairie Violet

Viola pubescens Yellow Violet

Zigadenus elegans White Camas

Zizia aurea Golden Alexanders

Appendix 2 – Rare Plants and Animals Found in Prairies and Savannas of Western Wisconsin (Wisconsin Natural Heritage Working List and Watch List)

These are species found in prairies and savannas of western Wisconsin, that are included by the Wisconsin DNR in the Wisconsin Natural Heritage Working List – a list of species known or suspected to be rare in the state.

The DNR Natural Heritage Inventory also has a watch list – of species they’re concerned about that have experienced a decline numbers either in the state or in their entire range.

Amphibians & Reptiles

Pickerel Frog –Special Concern

Timber Rattlesnake – Special Concern

Eastern Hog-nosed Snake – Watch List

Northern Leopard Frog –Watch List

Birds

Henslow’s Sparrow – Threatened

Yellow-breasted Chat – Special Concern

Grasshopper Sparrow – Watch List

Veery – Watch List

Black-billed Cuckoo – Watch List

Yellow-billed Cuckoo – Watch List

Bobolink – Watch List

Red-headed Woodpecker – Watch List

Vesper Sparrow – Watch List

Dickcissel – Watch List

Field Sparrow – Watch List

Eastern Meadowlark – Watch List

Blue-winged Warbler – Watch List

Butterflies & Moths

Ottoe Skipper – Endangered

Phlox Moth – Endangered

Juniper Hairstreak – Special Concern

Dusted Skipper – Special Concern

Gorgone Checkerspot – Special Concern

Columbine Duskywing – Special Concern

Leadplant Flower Moth – Special Concern

Pink Streak Moth – Watch List

Wild Indigo Duskywing – Watch List

Harvester – Watch List

Leonard’s Skipper – Watch List

Eyed Brown – Watch List

Cross-line Skipper – Watch List

Little Glassy-wing – Watch List

Hickory Hairstreak – Watch List

Plants

Dragon Wormwood – Special Concern

Kitten Tails – Threatened

Hill’s Thistle – Threatened

Arrowhead Rattlebox – Special Concern

Prairie Bush-clover – Endangered

Dotted Blazing Star – Endangered

Brittle Prickly-pear – Threatened

Clustered Broomrape – Threatened

One-flowered Broomrape – Special Concern

Prairie Ragwort – Special Concern

Prairie Fame-flower – Special Concern

Small Skullcap – Endangered

White Camas – Special Concern

Autumn Coral-root – Watch List

Solidago sciaphila – Watch List

Appendix 3 – Example prairie mix (showing both species diversity and seed density) from the O’Connor farm

[Deleted from the web version of this document — too dang hard to reformat. Sorry about that.]